ABSTRACT

Innovation is critical to improving society and is key to the cyber domain. The rapid growth of the internet has meant that tools for operating in cyberspace have constantly evolved. It has often been said, however, that the only innovation taking place in cyber warfare is in offensive operations. So where is the innovation for the defense? To effectively defend cyberspace against threats, is there sufficient defensive innovation? And if such innovation is truly happening, why does it seem as though attackers are always several steps ahead? To address these concerns, we examine four types of innovation. Sustaining and incremental innovations tend to generate improvements within existing systems but usually originate as reactive responses to market needs. Breakthrough and disruptive innovations target new markets and can proactively shape our environment in drastic ways. By understanding that clear distinctions exist within “innovation,” we can develop an innovation strategy to prepare for future cyber conflict. Rather than lament how cyber defense is failing, we can instead advance defensive innovations that will succeed. In this paper, we discover that nearly all offensive cyber tools, to include most computer viruses, worms, and other malware, fall into the disruptive realm—the type of innovations that are relatively cheap to produce, quicker to implement, and inherently more flexible because they utilize existing assets. Conversely, we find most defensive cyber capabilities, such as intrusion prevention systems and automated self-healing systems, are typically breakthrough innovations that are expensive, technologically more complex, and require extensive research. We believe that to systematically defend cyberspace, every type of innovation is needed to ensure an acceptable level of cybersecurity. In particular, by refusing to concede disruptive innovation to cyber threats and pursuing this type of innovation for the defense, we can prevail in future cyber conflict.

1. AN INNOVATION FRAMEWORK FOR CYBERSPACE OPERATIONS

As a nation, the United States (US) has prided itself on its innovative spirit, and its citizens have benefitted from the growth and progress that have resulted from its many innovations. Even in the U.S. Army, innovation has played a critical role in its past successes. As it looks to the future, the US continues to emphasize the importance that innovation has to “enable success, regardless of the missions assigned or the threats confronted” [1] When the word “innovation” is used, most people will think of inventions and ideas that have an impact on society. However, these types of inventions and ideas are only a part of the picture. There are, in fact, four areas of innovation that contribute to the success of an organization: sustaining, incremental, breakthrough, and disruptive. [2] By applying the innovation framework of these four distinct types, one can assess the gaps and identify the opportunities for competitive advantage. To prepare for future cyber conflict, the US must develop the right mix of defensive and offensive capabilities, which consists of a portfolio of innovations across the four distinct types. This paper uses the framework to categorize innovations in cyberspace to better understand the activities taking place in the defensive and offensive realms. Cyber innovations exist in all four types, but the deficit of defensive tools in the disruptive space might be providing the adversaries with the upper hand. Therefore, this paper emphasizes the importance of harnessing more disruptive innovations to not only improve the US military’s defensive capabilities but also to enhance the way we can all defend the cyber domain in future cyber conflict.

To gain a true appreciation for the innovations taking place in cyberspace, it is important to first gain a clear understanding of the types of innovation. There are a variety of frameworks that categorize innovation into four main types, such as those presented by Kalbach [3], Nielson [4], and Pisano [5]. These frameworks serve to explain innovation and make the point that each type of innovation requires a different strategy. This paper uses Wong and Sambaluk’s [2] framework to distinguish between the various innovations.

Sustaining and incremental innovations react to existing market needs and are typically the types of innovation that support a company’s bottom line. Successful innovation focuses on improving performance and efficiency of an established product and try to extend a product’s profit lifecycle for as long as possible. For example, each year automotive companies often introduce new

|

|

|

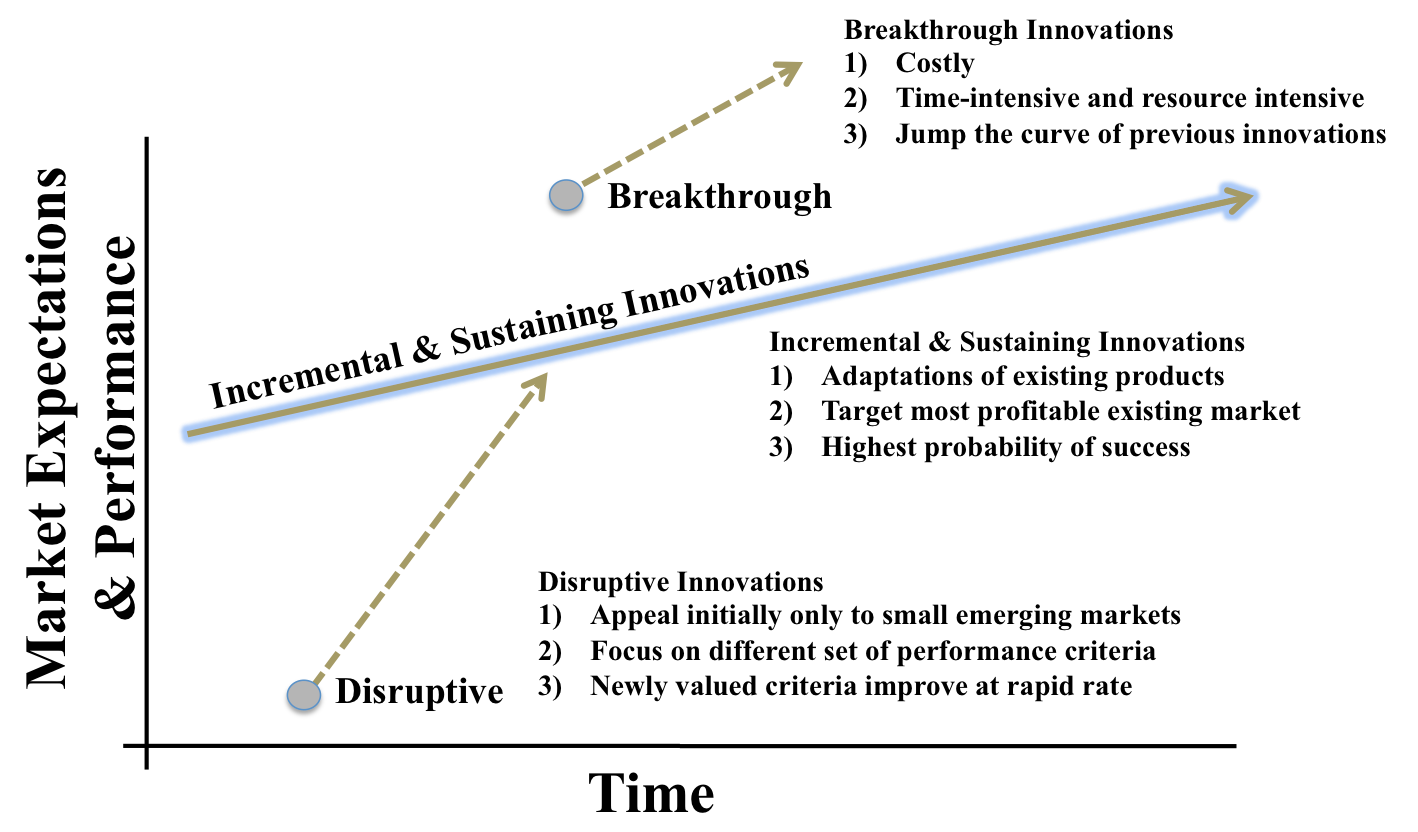

Fig. 1. Innovation Framework adapted from Wong and Sambaluk [2]

|

features on their cars that improve upon the previous year’s model. By touting the enhanced performance measures and new attributes, automotive companies aim to strengthen a product already in place. The household products market provides another example in which a company might make a cleaning product stronger and add more scent options to its current line of products to extend the shelf-life of a successful product. Incremental innovation is similar to sustaining in that it tends to react to existing market needs but is more evolutionary. Incremental innovation can be thought of as a tit-for-tat type cycle of innovation, in which one actor comes up with an innovation that beats out the competition; the competitor then responds by coming up with an even better innovation to up the level of play within an existing category. The evolution of smartphones in terms of added features like screen size, camera pixels, and built-in applications is an example of incremental innovation in that competing companies are consistently adding new features to increase their sales and share of the market. The fast food market provides another example in which restaurants are diversifying their menu choices to attract and retain consumers whose tastes change with diet and nutrition trends.

|

|

|

Fig. 2. Risk-Reward Comparison for Pursuing Different Types of Innovation. Adapted with permission from E.Y. Wong, K.R. Hutton, and R.F. Gagnon, “The Innovator’s Challenge: Can the US Army Learn to Out-Hack Those Who Attack Us in Cyberspace?” In D.V. Puyvelde & A.F. Brantly (Eds), US National Cybersecurity International Politics, Concept and Organization, Routledge.

|

While sustaining and incremental innovations are reactive to market needs, breakthrough and disruptive innovations are proactive. They seek to change the environment rather than adapt to the environment around them. Breakthrough innovations are cutting edge and represent a significant advancement in technological complexity or sophistication that jumps the curve of previous products and processes. Breakthrough innovation introduces a new product, causes product substitution, or introduces a new way of doing things that require a new skill base [6]. For instance, sequencing the human genome was a breakthrough in the field of science that took about 13 years, cost close to $3 billion, and created a new high-end market for genome sequencing [7]. The Global Positioning System (GPS) is another example of a breakthrough innovation that was developed by the United States government to provide geolocation capability that created a new military, civil, and commercial market around the world. While breakthrough innovations tend to be expensive to create, disruptive innovations are relatively cheap and revolutionary. Disruptive innovations also appeal to a new or underserved market and use assets that are readily available [8]. For example, home-based personal copiers disrupted large corporate printers; the large printers became so expensive and customized for expert use that it left the home and personal market underserved and ripe for disruptive innovation. Personal cellular phones are another example of a disruptive innovation that provided a new population of consumers with access to a communication product and service that was limited to fixed-line telephone availability and expensive portable phones.

Overall, the four types of innovation can be distinguished by how they impact a target market, compare in technological complexity, and whether or not they are proactive or reactive. An adaptation of Wong and Sambaluk’s [2] innovation framework for distinguishing the various types of innovation is shown in Fig. 1 that includes how the idea or innovation originates in terms of proactive and reactive. As discussed above, sustaining and incremental innovations target existing markets while disruptive and breakthrough innovations impact underserved markets or create new markets. Disruptive and sustaining innovations are less complex because they rely on systems and technologies that already exist while breakthrough and incremental innovations are more complex because they depend upon the research and development of new technologies.

Two additional dimensions – success rate and impact potential – can also be added to further distinguish the four types and provide insight into the potential risks and rewards of pursuing each type. Sustaining and incremental innovation has a high probability of success because they rely on an established market. Disruptive and breakthrough innovation have the opposite because they are charting new territory in developing a new market. Disruptive and breakthrough, however, have a higher impact potential than sustaining and incremental because they are creating a new market. These additional dimensions are shown in Fig. 2. It is essential to understand the characteristics and risks and rewards associated with each type of innovation to develop the best innovation strategy for outmaneuvering adversaries.

2. CATEGORIZING CYBER INNOVATIONS

Having a better understanding of the cyber innovations taking place can provide insights into what entails competitive advantage in cyberspace and how the US military can strengthen its cyber capabilities going forward. Throughout history, there have been examples of cyber innovations that fit within the four categories of innovation and can be considered an offensive or defensive tool. Offensive cyber technologies seek to infiltrate, exploit, or attack cyber infrastructure. Defensive cyber technologies seek to protect systems from any unauthorized access, actions, or attacks. Some examples of these innovations are discussed below and depicted in Fig. 3.

Breakthrough cyber innovations involve large technologically complex advances that often take considerable time and money to develop. The invention of Transmission Control Protocol/Internet Protocol (TCP/IP) can be considered a defensive breakthrough innovation. TCP/IP interconnected network devices on the Internet and revolutionized the way network communications were conducted by passing them through four separate layers: application, transport, network, and data link. Security controls exist at all four layers of the process, allowing for more protection than previously available. Breakthrough innovations are less common in the offensive domain, but the Stuxnet worm serves as an example. Stuxnet was a first of its kind digital weapon

that was developed for a specific target with the goal of physical destruction [9]. Stuxnet was part of a covert operation that was highly technical and created a new market for developing and using computer programs that could do more than merely hijack or steal information.

|

|

|

Fig. 3. Types of Cyber Innovations. (*Offensive Tool, ^Defensive Tool)

|

The faster pace and unique approach of disruptive innovation to utilize assets that already exist support more widespread innovation in cyberspace. One of the best examples of a disruptive innovation used for cyber defense is when US space agency NASA blocked all emails with attachments before shuttle launches to evade hackers impacting the mission [10]. NASA used a simple, low-cost solution to address a problem. Disruptive innovations are commonly used on the offensive side of cybersecurity with most malware being prominent examples. The overwhelming majority of malware has taken advantage of existing flaws within systems or software to achieve its malicious goals. For example, the I LOVE YOU virus was an infamous computer worm that originated in the Philippines. It spread by e-mail, arriving with the subject line "ILOVEYOU" and the attachment "LOVE-LETTER-FOR-YOU.txt.vbs." If the attachment was opened, the computer became infected. Many recipients were tricked into opening the infected attachment because Microsoft Windows concealed the extension of the file as a seemingly innocuous text file.

Because sustaining innovations improve a product that has an established place in a market, the use of antivirus software is a common defensive application of sustaining innovation. Antivirus software for desktops usually includes a firewall, virus detection technologies, and other security software. Antivirus software companies release updates, additions, and new iterations of their security software to extend the life of their products for the common consumer. On the offensive side, an example of a sustaining innovation is the usage of subsequent versions of viruses or worms that have proven to successfully exploit a computer system. Similar to automotive companies making performance tweaks and adding new features to a popular model, cyber adversaries create updated viruses and worms to improve their effectiveness.

In the cybersecurity domain, incremental innovations are a direct result of the actions of hackers and defenders responding to one another. In the US, the Computer Emergency Response Team (CERT), which was created in response to one of the first computer worms known as the Morris Worm, is an example of incremental defensive innovation. The CERT was established to alert computer users of network security issues in an attempt to prevent another devastating Morris Worm incident [11]. Today, the CERT provides alerts and avoidance guidance for cybersecurity incidents as a security sustaining tool. In the offensive domain of incremental innovation, software bugs, or flaws in the computer programming, are an example. Perpetrators exploit software bugs until detected by the software company. The software company responds back by releasing a patch to fix the error in the system. Malicious users start the cycle over again by looking for bugs within the patched code or another software program.

Over time, successful breakthrough or disruptive innovations can become sustaining or incremental innovations as mainstream markets gradually adopt them. It is also important to note that some innovations do not directly fall into one category and might overlap multiple categories when initially developed. For example, the Creeper Virus can be considered to be both disruptive and breakthrough. The Creeper was developed to move between mainframe computers by self-replicating or copying itself and displaying the message, “I’M THE CREEPER: CATCH ME IF YOU CAN.” This virus was a breakthrough innovation because it was first of its kind and created a new market for developing and using computer programs that could duplicate themselves in a rogue manner. However, it was also disruptive because it did not use any new science or any expensive equipment. The virus simply exploited the systems it was running on and changed the environment of the system to perform a specific function. As the Creeper Virus demonstrates, the distinctions between each type of innovation can blur. However, the overall logic to categorize offensive and defensive tools is useful in understanding the location of capability gaps.

3. DEFENSIVE DISRUPTIVE INNOVATIONS TO FIGHT FUTURE CYBER ATTACKS

If the innovation of all four types is occurring in cybersecurity as Fig. 3 illustrates, why does it seem as though the attacker always seems to be at least one step ahead of the defender? In comparing offensive versus defensive tools in Fig. 3, it is evident that there is a lack of defensive tools originating in the disruptive space. By failing to focus on developing disruptive defensive cyber tools, the US military is arguably conceding the advantage of speed and agility to its adversaries. With a low barrier to entry, an adversary can take advantage of problems and loopholes that exist within systems by using malware that is already proven and even sold on the market; therefore, an adversary can achieve an effect without worrying about the complexity of the tool, and the cost is relatively low. “Due to the decreasing cost of automation and cloud-based capabilities, a growing marketplace of threat actor information sharing, and the ever-increasing attack surface with vulnerabilities growing in proportion due to the ‘Internet of Things’ phenomenon, the Attacker’s job is getting cheaper and easier every day” [12]. This outlook suggests that the cyber environment is changing so rapidly with disruptive malware, there is no room for any type of innovation other than incremental evolutions to adapt to system breaches. The current system for cyber defense may be failing because the US military is not capitalizing on the value of innovating within the disruptive space. Although spending millions of dollars to research and develop the latest reactive cyber equipment and technology does provide benefits, there should also be researchers who develop proactive solutions that are cheap and relatively simple. The US military must develop defensive innovations that can change the environment at such a pace that offensive tools like computer viruses, worms, Trojan horses and other malware can no longer keep up and the cost of doing so becomes prohibitive. By fostering more disruptive innovation, the US military can develop a more comprehensive innovation portfolio that balances the offensive and defensive capabilities needed to prepare for future cyber conflict.

To foster more disruptive innovation, the US military must adopt an experimental mindset to develop relatively inexpensive tools that are simple and accessible to an underserved or new market, and that might experience failures along the way. History provides examples that the US military can be an innovative force that embraces the disruptive warfare paradigm [2]. For example, joint operations, as perfected in Desert Storm, brought the Army, Navy, and Air Force capabilities together as part of the AirLand Battle Concept, which extended offensive action to the fullest extent possible based on all available military assets. Military offensive operations were no longer limited by a focus on close battles where armies came in contact with one another; the operational reach of bomber and fighter aircraft permitted the US to devote military resources to additional objectives well beyond the front lines of traditional warfare [13]. There are many other examples that demonstrate the US military can develop disruptive offensive capabilities, but future cyber conflict will require the US military to learn how to develop disruptive defensive capabilities as well. The US military can begin to develop such capabilities by leveraging and expanding upon current disruptive innovation in the cyber community that is focused on increasing basic cyber education for the general public, developing partnerships for better information sharing and intelligence exchange, and harnessing the potential of the cloud computing architecture.

Basic cyber education for the general public is an example of disruptive innovation that offers economies of scale, uses a system that is already in place, does not require tremendous expense, and targets an underserved market. The importance of initiating a national public awareness and education campaign to help the American people understand the need for and value of cybersecurity is not a new idea. In fact, it was a key recommendation by President Obama’s National Security and Homeland Security Advisors in the 2009 Cyberspace Policy Review [14]. A strong awareness campaign could decrease vulnerabilities in networks attributed to human error. The Online Trust Alliance’s 2015 Data Protection & Breach Readiness Guide, stated that employees caused 29% of data breaches between January and June of 2014 and 90% of the breaches that occurred during that timeframe could have been prevented by implementing best practices for data protection [15]. By supporting efforts led by the US government to educate the general public, the US military could help the nation develop a defensive capability to decrease the success rate of adversaries by simply increasing awareness of best practices for securing information networks.

To develop a defensive tool to prepare for future cyber conflict, the US military could also participate in cyber education efforts currently underway and ultimately develop an awareness campaign of its own. GenCyber, a program funded jointly by the National Security Agency and the National Science Foundation, is a cyber awareness education program that targets K-12 students and teachers [16]. Modeled after a language camp program, GenCyber is disruptive in that it targets K-12 students and teachers, an underserved population regarding cybersecurity training. This is an example of a low cost and low technical solution that has high impact potential and provides a product for customers outside of the expensive breakthrough market. By working to create a similar culture of awareness around cybersecurity for the general public at large and underserved Department of Defense audiences, the US military could help strengthen cyber defenses by reducing human errors, by making basic cybersecurity cheap and ubiquitous, and by educating a new community of cyber defenders that will only grow in size. This defensive capability would be both disruptive and durable.

Strengthening partnerships with the private sector to enhance information sharing and intelligence exchange is another avenue for the US military to increase its disruptive defense tactics because “neither the government nor the private sector can properly protect the relevant systems and networks without extensive and close cooperation” [17]. The Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) sponsored an initiative called InfraGard is an example of a program that is creating a channel for businesses, academic institutions, state and local law enforcement agencies, and other participants to share information about vulnerabilities and solutions that are not discussed in the public domain. In a talk at the 2016 CyCon US Conference, Shawn Henry, President of CrowdStrike Services and Chief Security Officer, noted that to be more disruptive, public-private partnerships should use the information from InfraGard to not only flag breaches and technical vulnerabilities but also analyze why those breaches occurred to better understand the failure points. The knowledge gained from those failure points then becomes actionable and can foster the development of defensive solutions that can be shared across government and industry. Using platforms like InfraGard that have already been established, pulling new information out of them, and then providing that information back is not technologically complex or expensive. This feedback loop would target the underserved industry partners willing to risk public exposure and liability for stronger cyber defenses. Over time, this feedback loop could establish new market performance criteria and establish collaboration norms across the government and private sector.

At its very core, activity in cyberspace is driven by human behavior to gain a competitive advantage, and additional intelligence through partnerships about breach activity could also help the US military better understand the behavior of adversaries. Colonel Patrick M. Duggan discusses the importance of understanding what drives human action in cyberspace “as a vehicle to identify conflicts earlier, seize opportunities to steer, and potentially, tamp down violence” [18]. To adequately defend our digital societies, it is essential to understand the competition to get ahead of, and not just react to adversaries. Intelligence exchange through partnerships could foster that understanding and make that knowledge accessible to a wider audience of consumers in need of building up cyber defenses. By partnering with industry to identify failure points and exchange information and higher level intelligence about breaches, the US military could strengthen its ability to defend against cyber conflict by creating a shared space for the development of more disruptive techniques, tactics, procedures, and technologies, foster interoperability between the public and private sector, and establishing norms for cyber collaboration.

Improving situational awareness by better understanding one’s network and system can be a way to quickly identify and defend against cyberattacks. With 55% of organizations across industries and the world now using some form of cloud computing [19] and US government agencies moving to cloud computing [20], the US military could take advantage of the same decreasing in cost capabilities that adversaries are using for cheap and easy exploits to develop defensive capabilities against them. Cloud computing, which includes infrastructure as a service (IaaS), platform as a service (PaaS), software as a service (SaaS), and security as a service (SECaaS), is an emerging market that creates a breeding ground for disruptive innovations. By developing software programs compatible with cloud computing architecture, entrepreneurs can compete with established software companies for business because consumers can quickly and cheaply download products. These cyber services originated as complex and customized in-house solutions for security and storage to large banks, industrial corporations, technology companies, and sensitive government agencies. Today, companies are targeting the underserved market of small businesses and individual users with these cyber services as a simple, low-cost solution to outsourcing security and storage among other services. By understanding the landscape and architecture of the cloud computing market, the US military could foster conditions that support disruptive innovation. For example, information security practitioners, who are exploring the nooks and crannies of this new information technology infrastructure, are looking for ways to exploit vulnerable side-channels to fix them. The US military should partner with individuals and entities doing this to develop better defensive techniques and knowledge of vulnerabilities. The US military could also experiment with current methods of big data and pattern analysis, off-the-shelf technology for an automated response, and intelligence from partners to determine what combination of those capabilities could provide stronger situation awareness and attack response mechanisms. As different low cost and available techniques are used to explore the cloud computing landscape, the US military might have a high failure rate, but success could yield high impact value by providing defensive capabilities that could be shared across the diverse range of cloud computing customers.

To be proactive in the cyber domain, the US military must embrace a mindset for disruptive innovation that considers simple and inexpensive ways to thwart adversaries. Disruptive innovations are arguably not the traditional innovations that most people think of in terms of solutions that are sophisticated, complex, and highly technical. Disruptive innovation is about leveraging ingenuity, imagination, and experimentation to make the best use of readily available resources in new ways that once implemented can be executed quickly and advance at a rapid rate to combat against cyber adversaries. Disruptive ideas like increasing awareness through public education and strengthening collaboration and sharing amongst the cyber community are not breakthrough ideas, but they have high impact potential to improve cyber defenses. Fig. 4 illustrates how a successful disruptive innovation can advance rapidly once adopted by the mainstream and create new market and performance expectations. By seeking and exploring new ideas, processes, and technologies from the cyber community, the US military can begin to develop more disruptive cyber defense capabilities.

Fig. 4. Innovation Framework for Market Expectations and Performance versus Time. *Framework adapted from J. Bower and C. Christensen, “Disruptive Technologies: Catching the Wave,” Harvard Business Review, Jan-Feb 1995, 43-53.

4. CONCLUSION

In cyberspace, milliseconds make a difference. As William J. Lynn III states in his article The Pentagon’s Cyberstrategy, “Cyberwarfare is like maneuver warfare, in that speed and agility matter most. To stay ahead of its pursuers, the United States must constantly adjust and improve its defenses” [21]. The world is currently at a tipping point where the speed of adversarial offensive cyber ingenuity and innovation is outpacing the development of US military defensive cyber capabilities. To address this, the US military ought to develop more disruptive innovations to protect the core of our cyberspace. It is important that all types of innovation, however, take place to promote the greatest chance of success to defend against cyberattacks. Sustaining innovations focus on improving what we already have, and incremental innovations focus on adapting our current technology to the changing world. Breakthrough innovations, where the US government arguably excels, are vital because they are at the forefront of the future and bring us ideas and technologies that change the environment. Disruptive innovations are also critical because they use current systems and processes to produce unimaginable outcomes and results. The risk in not diversifying research efforts and innovating in all four areas to prepare for future cyber conflict is giving adversaries a competitive advantage that is avoidable. The US military can best protect cyberspace by understanding distinctions exist within innovation and working to develop innovations across all types.

BIOGRAPHY

Katherine Hutton was formerly a Special Advisor at the United States Secret Service. She graduated from Duke University with a B.S. in biology and minor in chemistry and holds an M.B.A. from the Duke University Fuqua School of Business Cross Continent Program. She is currently pursuing a Master of Professional Studies in Cybersecurity Strategy and Information Management at George Washington University.

Lieutenant Colonel Ernest Y. Wong is a Military Intelligence Officer in the U.S. Army who is currently serving both as the Chief of Staff at the Army Cyber Institute and as an Assistant Professor with the Department of Systems Engineering at West Point. He graduated from the United States Military Academy with a B.S. in economics, and he holds a M.S. in management science and engineering from Stanford University, a M.A. in education from Stanford University, and a Master of Military Science from the Mubarak al-Abdullah Joint Command and Staff College in Kuwait. He had the opportunity to work as a NASA Summer Faculty Fellow and has served in overseas deployments to Iraq, Kuwait, and the Republic of Korea. His research interests include disruptive innovations, cyber resiliency, and the application of systems engineering tools for resolving complex real-world problems.

2nd Lieutenant Ryan F. Gagnon is a Signal Corps officer serving the New York Army National Guard. He is a graduate of Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute where he received his Bachelor of Science in Computer and Systems Engineering. 2LT Gagnon has contributed to the efforts of the Army Cyber Institute as a research volunteer and was a coauthor for the article “Why Government Organizations Don’t Care: Perverse Incentives and an Analysis of the OPM Hack” published in the Heinz Journal at Carnegie Mellon University. His interests include cyber defense policy and military involvement within the cyber domain.

NOTES

[1] R.T. Odierno and J.M. McHugh, “The Army Vision: Strategic Advantage in a Complex World,” United States Army, 2015.

[2] E.Y. Wong and N. Sambaluk, “Disruptive Innovations to Help Protect against Future Threats,” Proceedings of the 2016 CyCon U.S. Conference, Washington, District of Columbia, October 21-23, 2016.

[3] J. Kalbach, “Clarifying Innovation: Four Zones of Innovation,” Experiencing Information, June 3, 2012, https://experiencinginformation.wordpress.com/2012/06/03/clarifying-innovation-four-zones-of-innovation/.

[4] J. Nielson, “The Four Types of Innovation and The Strategic Choices Each One Represents,” The Innovative Manager, October 10, 2013, http://www.theinnovativemanager.com/the-four-types-of-innovation-and-the-strategic-choices-each-one-represents/.

[5] G.P. Pisano, “You Need an Innovation Strategy,” Harvard Business Review, 93, no. 6, 2015, 44-54.

[6] C.M. Christensen and M.E. Raynor, The Innovator’s Solution: Creating and Sustaining Successful Growth. Boston: Harvard Business School Press, 2003.

[7] M.L. Tushman and P. Anderson, “Technological Discontinuities and Organizational Environments,” Adminstrative Science Quarterly, no. 3, 1986, 439-465.

[8] T. Lewis, “Human Genome Project Marks 10th Anniversary,” Live Science, April 14, 2013, http:www.livescience.com/28708-human-genome-project-anniversary.html.

[9] K. Zetter, “An Unprecedented Look at Stuxnet, The World’s First Digital Weapon,” Wired, November 2014, http://www.wired.come/2014/11/countdown-to-zero-day-stuxnet/.

[10] NATO Review Magazine, “The history of cyber attacks – a timeline,” 2016, http://www.nato.int/docu/review/2013/cyber/timeline/EN/index.html.

[11] B. Daya, “Network Security: History, Importance, and Future,” University of Florida Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering, 2013.

[12] J. Davis, “Four Imperatives for Cybersecurity Success in the Digital Age: We Must Flip the Scales,” The Cyber Defense Review, 1, no. 2, 2016, 31-40.

[13] Executive Office of the President of The U.S., “Cyberspace Policy Review: Assuring a Trusted and Resilient Information and Communications Infrastructure,” 2009, https://www.dhs.gov/sites/default/files/publications/Cyberspace_Policy_Review_final_0.pdf.

[14] J. L. Romjue, “The Evolution of the Airland Battle Concept,” Air University Review, May-June 1984, http://www.au.af.mil/au/afri/aspj/airchronicles/aureview/1984/may-june/romjue.html.

[15] Online Trust Alliance, “2015 Data Protection & Breach Readiness Guide,” Online Trust Alliance, February 2015.

[16] GenCyber, “About GenCyber,” 2016, https://www.gen-cyber.com/about/.

[17] K.B. Alexander, J.N. Jaffer, and J.S. Brunet, “Clear Thinking About Protecting the Nation in the Cyber Domain,” The Cyber Defense Review, 2, no. 1, 2017, 29-36.

[18] PwC, “The Global State of Information Security Survey 2015,” CSO Magazine, CIO Magazine, September 2014.

[19] P.M. Duggan, “U.S. Special Operations Forces in Cyberspace,” The Cyber Defense Review, 1, no. 2, 2016, 73-79.

[20] V. Kundra,“Federal Cloud Computing Strategy,” The White House, February 2011.

[21] W.J. Lynn, “Defending a New Domain,” Foreign Affairs, September/October 2010, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/united-states/2010-09-01/defending-new-domain.