Tinker

As a child, I loved when birthday time came around. Not only mine, mind you – but also my brother’s. Whenever he received a shiny new radio-controlled car, it meant an afternoon full of disassembly and exploration was in my future. I took a certain delight in tinkering, hacking, and repurposing all kinds of materials, often to the chagrin of my younger sibling. In the same way that my childhood hero, Angus MacGyver, saw the ordinary paperclip as the life-saving ingredient to a just-in-time solution, I envisioned the fantastic lives that regular household materials could live. This insatiable hunger to find out what’s inside has undoubtedly driven me to my current career path as a Cyber Officer. While there was no path becoming a Cyber Officer when I first joined the military, I believe my interests in technical exploration positioned me well to join the Army’s newest branch. While the Army is placing significant resources into growing Cyber-related career fields by refining doctrine and funding excellent training opportunities, it’s also important for the service and its prospective technical leaders to leverage the well-established community of hobbyists known as makers. According to Make Magazine:

Many makers are hobbyists, enthusiasts or students (amateurs!)–but they are also a wellspring of innovation, creating new products and producing value in the community. Some makers do become entrepreneurs and start companies.

These two communities, cyber professionals and makers, value many of the same skills and attributes. In fact, Cyber Officers may find that participation in the maker movement can bring significant benefit in providing an enjoyable outlet that reinforces technical fundamentals.

Maker

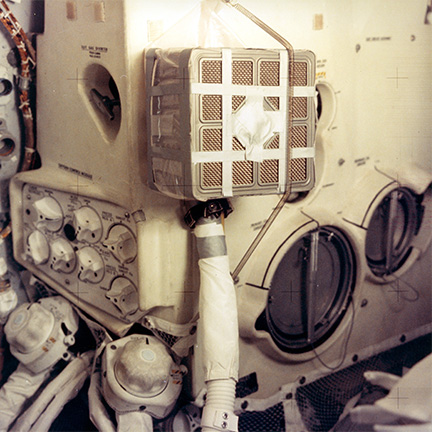

Many accomplished crafters, musicians, scientists, engineers, students, builders, and software developers distinguished themselves as makers or “hackers” by finding unique solutions to difficult problems. A prime example of such ingenuity was made popular in the 1995 film Apollo 13. Named the Greatest Space Hack Ever by Popular Science Magazine, the improvised solution provided by Apollo XIII’s ground-based Crew Systems Division (CSD) after an explosion damaged critical parts of the craft was nothing short of brilliant. With time and oxygen running short, the orbiting crew members of the manned mission received the detailed steps for creating the device from the CSD with items known to be onboard. The instructions for making the makeshift “mailbox” rig required use of various random parts, including the cover from a flight manual, socks, and components from flight suits. Though the overall mission was a failure in that there was no lunar landing as planned, this “successful failure” would later be described as “NASA’s finest hour”[1] in that all three astronauts, James A. Lovell, Jack L. Swigert and Fred W. Haise, made it back to Earth safely. In an interview after the successful splashdown of the craft, Ed Smylie, CSD Chief noted, “it was pretty straightforward, even though we got a lot of publicity for it and [President Richard M.] Nixon even mentioned our names. I always argued that that was because that was one you could understand – nobody really understood the hard things they were doing. Everybody could understand a filter. I said a mechanical engineering sophomore in college could have come up with it. It was pretty straightforward. But it was important.”[2] Though less elegant than production-level solutions, the team’s results, given the time crunch and lack of resources, demonstrated superior synthesis skills. NASA’s exemplar of ingenuity wasn’t based on hunches: it required a firm grounding in formal training combined with the quick thinking of a team dedicated to success.

Solder

Cyber Officers, like the best makers, must also be grounded in solid theoretical understanding and practical experience. Ohm’s Law and knowing how to solder, for example, are fundamentals that are hard to get around when dealing with any applied electrical engineering. Makers and engineers aren’t mutually exclusive communities. In fact, the maker mindset embraces the traditional values of effective education — problem solving, deep and direct engagement with content, critical thinking, collaboration, and learning how to learn. Although formal education is often the most effective way of achieving a high level of technical understanding, having technical hobbies is an excellent complement. Such a balance can be achieved by joining a makerspace to maintain fundamentals and keep pace with current trends. Since skills in technical fields atrophy at a more rapid rate than in other fields, it’s particularly important that Cyber Officers take initiative to never stop learning. Like makers, Cyber Officers must not only be willing to stay current within their areas of expertise, but also be open to exploration outside of their comfort zone.

Try

New tools and technology demonstrated at events like Maker Faire provide makers with exciting ways to turn their ideas into something real. The current offerings of 3D printers, robotics, microprocessors, computing devices, and programming languages are increasingly affordable. One such example are Computer Numerical Control devices, or CNCs for short. These electronically controlled routing and carving devices could previously only be found in the most advanced workshops. In 2014, a turnkey CNC system could be had for just under $1000. Additionally, since information is easier than ever to share, learning how to use the devices aren’t as difficult as in the past – plus, 3D models and sketches are freely available on sites such as Thingiverse. Taking advantage of increased availability of hardware and software isn’t only restricted to the physical – one effective technique for Cyber Officers may be to build a sandbox at home in which to practice new techniques using a platform such as the free VMware vSphere Hypervisor. Low-cost hardware and software, and freely available high-quality instructions facilitate learning in a safe environment. Furthermore, reduced barriers to entry in traditionally costly practices make it easier to explore advanced technologies, allowing individuals to transform curiousity into real skills and maintain those skills more affordably and easily. This, in turn, increases confidence, competence and agility, key attributes for success in any field.

Looking Forward

My path to becoming a Cyber Officer was supported by good timing and great mentors, but I believe that my background as a maker also played a significant role in leading me to where I am today. As the President recently noted in his proclamation for the National Day of Making, it’s critical that the nation, including the Army, support our makers by recognizing their interests and embracing their skills.

This is a country that imagined a railroad connecting a continent, imagined electricity powering our cities and towns, imagined skyscrapers reaching into the heavens, and an Internet that brings us closer together. So we imagined these things, then we did them. And that’s in our DNA. That’s who we are. We’re not done yet. And I hope every company, every college, every community, every citizen joins us as we lift up makers and builders and doers across the country.

President Obama

Remarks at the White House Maker Faire, National Day of Making on June 18, 2014

There should be a clear path for officers that have the interest in making and the aptitude to excel at proving technical solutions. Cyber can be that branch to create such a path. One example of concrete steps that the Army is taking is the significant work already being done at the Army Cyber Institute to grow future cyber warriors. The Cyber Leader Development Program (CLDP), established by ACI Director of Education Research, LTC David Raymond, provides a means to identify and assess of candidates to commission into the Army’s Cyber branch. Cadets enrolled in CLDP are assessed in technicial and non-technical dimensions and assigned a mentor to carefully monitor their academic and personal growth while at the United States Military Academy. CLDP, as an Additional Skill Identifier generating program, is already being tailored for use across the Army. Programs such as CLDP are an excellent examples of the Army’s improved appreciation of individual’s talents and interest; talents, which when properly leveraged, improve the overall posture of our force and country.

[1] Foerman, Paul; Thompson, Lacy, eds. (April 2010). “Apollo 13 – NASA’s ‘successful failure'” (PDF). Lagniappe (Hancock County, MS: John C. Stennis Space Center) 5 (4): 5–7.

[2] http://www.jsc.nasa.gov/history/oral_histories/SmylieRE/SmylieRE_4-17-99.htm