With an increased national awareness that the critical infrastructure which keeps our country running is surprisingly vulnerable—not just to physical attacks, but also to cyberattacks that can be initiated from anywhere in the world—the State of Indiana executed CRIT-EX 16.2 on the 18th and 19th of May, 2016, at the Muscatatuck Urban Training Center. This cyberattack readiness exercise focused on improving Indiana’s overall security and responsiveness of its critical infrastructure to face advanced cyber disruption of essential water utility services – presenting an extreme public safety threat. Indiana, like the rest of the country, understands it has a short window of opportunity to prepare for a major cybersecurity event that, if successful, could be as devastating as a major earthquake or tornado. In order to effectively prepare for such a scenario, Indiana’s cybersecurity stakeholders realized they had to build high-functioning, collaborative networks that span the public and private sector. By working to collaborate on high-risk cyber issues, organizations throughout Indiana are elevating their response postures, and preparing to ratchet up their ability to confront the threats of tomorrow [1].

CRIT-EX 16.2 attendees tourthe FBI’s national Mobile Command Center (photo by Ernest Wong)

“This exercise explored the intersection between critical infrastructure and cyber security,” explained Jennifer De Medeiros, Emergency Services Program Manager for the Indiana Department of Homeland Security [2]. The Indiana Department of Homeland Security (DHS) in conjunction with the Indiana National Guard, Indiana Office of Technology, Cyber Leadership Alliance, and over 16 other public and private partners developed this controlled functional cyberattack exercise allowing participants to deploy resources and communicate with response partners to mitigate adverse effects and expedite recovery. Additionally, CRIT-EX is the first joint public-private partnership simulating responses to cyberattacks on the Muscatatuck water treatment plant, with expert programming and cybersecurity teams acting as cyberterrorists who attack the facility’s Supervisory Control and Data Acquisition (SCADA) systems [3]. Because most of these systems are controlled by civilian organizations that are not tasked with the defense of the nation’s infrastructure, the SCADA systems are not adequately hardened or secured from cyber hackers who could access their data, compromise their systems, and cause serious damage. Consequently, such hackers can hit these systems with malware and false commands resulting in real damage in the physical world, causing machinery and other systems to malfunction or shut down. As a consequence, a small cyberattack on one part of the system can lead to a major disaster over a much wider area since much of our infrastructure is interconnected [4].

During the two-day exercise, members of Frakes Engineering, a systems integration company that specializes in designing and integrating control systems, and cyber security teams from Pondurance and Rook Securities acted as cyber terrorists intent on disrupting and damaging the Muscatatuck water treatment plant. Participants helped to clearly expose and vividly illustrate just how vulnerable our SCADA systems are to a persistent cyber adversary. Additionally, representatives from the FBI SCADA Fly Team, Industrial Control Systems Cyber Emergency Response Team (ICS-CERT), the 172nd Army National Guard Cyber Protection Team, and the Indiana Information Sharing and Analysis Center (ISAC) were on hand to practice coordinating initial recovery efforts and offer professional response guidance.

Members of Rook Security, Pondurance, and the Indiana NG Prepare for CRIT-EX 16.2 (photo by Brad Staggs)

Tony Vespa, board member of the Cyber Leadership Alliance, remarked, “Getting more than 18 public and private entities to willingly participate in an exercise such as this was a huge challenge, and the team had to essentially create a cyber stone soup to get everyone to the table.” Vespa highlighted that CRIT-EX had three very important aspects that differentiate it from other cyber exercises: use of a common language for all exercise participants, a strict adherence to keeping all uncovered cyber vulnerabilities confidential and private, and the employment of real-time and complex cyberattack vectors in which the participating organizations could experience not only disruptions in the cyber domain, but actually see resulting consequences in the physical domain as well.

In order for all of the different entities to communicate effectively with one another throughout the exercise, the participants all agreed on a common language. After months of struggling to understand the unique requirements of each of the various critical infrastructure sectors, the planning team decided that the US-DHS Homeland Security Exercise and Evaluation Program (HSEEP) would serve as the common and unifying exercise language. Ultimately, this proved invaluable to the success of the exercise.

As participation increased to include all six of Indiana’s major water companies, privacy issues soon began to surface. Participating organizations and companies became extremely concerned about the disclosure of cyber vulnerabilities during the exercise that would leave their systems exposed. Additionally, the risk of unmasking regulatory compliance deficiencies left many wondering whether a water utility would be willing to accept such a potential risk. The exercise planners tackled these serious concerns by addressing them at the outset. First, participating teams from the various water companies were staggered throughout the exercise so that no team would have the chance to observe the deficiencies of another team. Trained observer teams from Indiana University, Purdue University, and the Indiana National Guard were all vetted, and served as neutral third-party evaluators. Additional evaluators came from the ranks of the Indiana InfraGard, a cooperative undertaking between the FBI and an association of businesses, academic institutions, and state and local law enforcement organizations dedicated to increasing the safety and security of Indiana and US critical infrastructures [5]. Finally, Red Team debriefings and after action reviews (AARs) were conducted in closed-room session at the end of the exercise, where all teams were informed that all notes, recordings, and images pertaining to a team’s performance would be returned or destroyed at the end of each AAR. Creating, emphasizing, and delivering on this level of confidentiality for CRIT-EX 16.2 engendered greater trust between all the organizations involved.

The final aspect which truly set CRIT-EX 16.2 apart from other cybersecurity exercises was that it linked virtual cyber security disruptions to actual physical disruptions at the Muscatatuck Urban Training Center. Cyberattack vectors were conducted in real-time on a fully functional water treatment plant; the effects of those virtual attacks were monitored from a control room fitted with screens displaying not just systems controls, but also closed circuit monitors showing water main disruptions and spillage based on the cyber hacker’s manipulation of the utility’s SCADA system. The participating teams consisted of system operators, executives, and supervisors familiar with incident response plans, which provided a multi-echelon perspective on both the cyberattack and its physical effects. Adding to the exercise complexity was the selection of the evaluation criteria used to judge the effectiveness of each water utility’s in-place cybersecurity measures. To help alleviate concerns from the participating water utilities that new standards were not being created specifically for the exercise, the CRIT-EX 16.2 planners emphasized key principles of the Homeland Security 32 core capabilities [6], and evaluated cyber security controls and measures using National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) recommendations for the security of industrial control systems (ICS) [7] and the American Water Works Association’s (AWWA) standards [8].

Exercise Controllers Describe the Effects of a Cyberattack on a Water Company’s SCADA Systems (photo by Brad Staggs)

Water plant superintendents and operators who attended and participated in this real-world exercise left with a more comprehensive understanding of the importance that the AWWA places on key areas of process control, which include:

- Governance and risk management,

- Business continuity and disaster recovery,

- Server and workstation hardening,

- Access control,

- Application security,

- Encryption,

- Telecommunications, network security, and architecture,

- Physical security of process control system (PCS) equipment,

- Service level agreements (SLA),

- Operations security (OPSEC),

- Education, and

- Personnel security [9].

Additionally, the participants and attendees gained a better appreciation for the ten basic cybersecurity measures that the Water Information Sharing and Analysis Center (WaterISAC) has espoused to improve cybersecurity:

- Maintain an accurate inventory of control system devices and eliminate any exposure of this equipment to external networks,

- Implement network segmentation and apply firewalls,

- Use secure remote access methods,

- Establish role-based access controls and implement system logging,

- Use only strong passwords, change default passwords, and consider other access controls,

- Maintain awareness of vulnerabilities and implement necessary patches and updates,

- Develop and enforce policies on mobile devices,

- Implement an employee cybersecurity training program,

- Involve executives in cybersecurity,

- Implement measures for detecting compromises and develop a cybersecurity incident response plan [10].

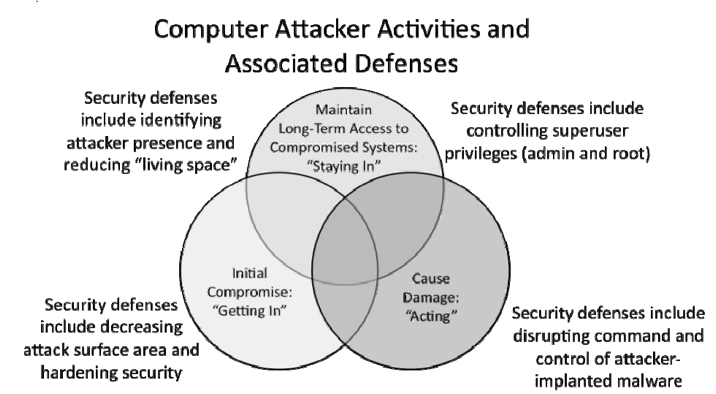

Figure 1: Types of Computer Attacker Activities and Controls Designed to Thwart the Attacks [11]

With a “Cyber 9/11” and a “Digital Pearl Harbor” at the forefront of homeland security discourse today, Indiana’s CRIT-EX 16.2 has helped to illuminate not only how devastating it can be when we lose control of the computer systems that manage our critical infrastructure, but also just how easy it can be for adversaries to hack their way into our SCADA systems. The exercise was an eye-opening experience for many of the attendees to witness in real-time just how quickly and furtively an advanced persistent cyber threat can compromise key control systems and damage critical infrastructure. Perhaps most importantly, CRIT-EX 16.2 was a transformative learning experience that has helped to equip utility executives and operators with improved cyber control measures (see Figure 1) that make it more difficult for cyberattacks to gain and maintain access, improve readiness, and help bolster our national security.