Joint force commanders exercise mission command across all domains to include land, air, maritime, space, and cyberspace. According to joint doctrine, mission command involves the conduct of military operations through decentralized execution,[1] and this demands that leaders at all echelons exercise disciplined initiative to accomplish missions.[2] However, in the case of military operations in cyberspace, there are aspects of mission command that are not yet fully developed for the joint force.[3] For instance, the emphasis on delegation and decentralization are not always appropriate for situations involving the employment of national level cyberspace capabilities designed to create effects in support of unified action.[4] Army forces are currently incorporating cyberspace as an “operational domain,”[5] and commanders understand how this effort has direct implications for their exercise of mission command in support of unified land operations.[6] In the absence of an operational example, past and current conditions on cyberspace integration will be discussed along with the mission command principle of creating shared understanding.

Cyberspace in Retrospect

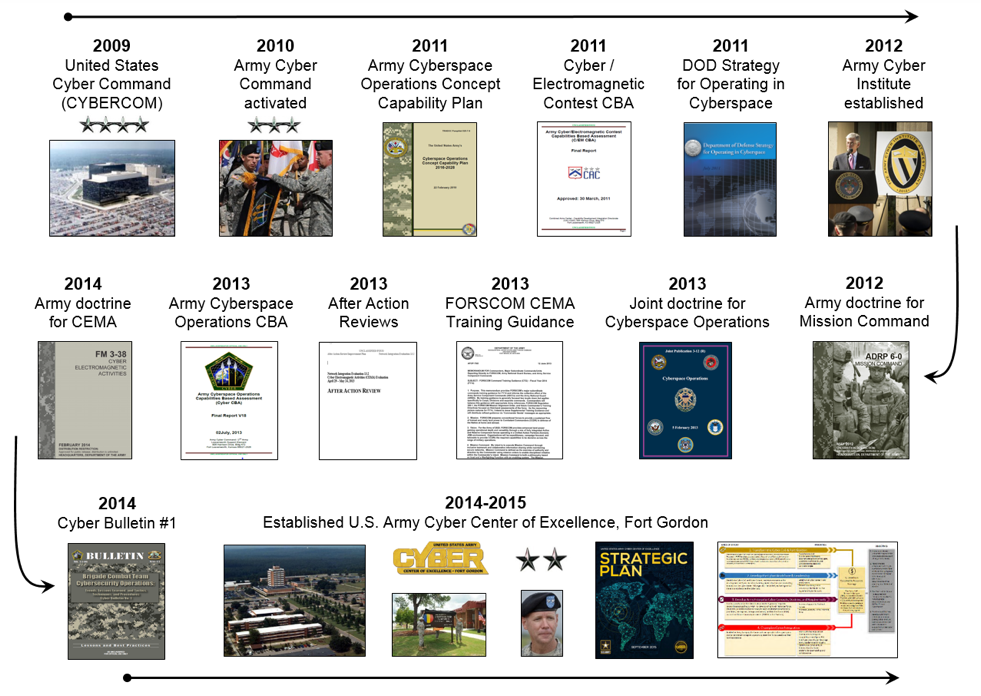

It is important to consider key events in recent history that have shaped how commanders currently exercise mission command in and through cyberspace. In 2009, national level discussions focusing on cyberspace gained remarkable momentum following the Cyberspace Policy Review, a comprehensive review to assess US policies and structures for cybersecurity.[7] The findings from the review led to the development of action plans to address shortfalls such as cybersecurity-related strategy, policy, and implementation.[8] These action plans guided the newly formed United States Cyber Command (USCYBERCOM). Figure 1 depicts a chronological flow of key joint and Army activities and published documents integral to the evolution of cyberspace operations.

Figure 1. Key Events and Documents

In 2010, the U.S. Army Cyber Command (ARCYBER) was established, and efforts were launched to expand research and development of cyberspace capabilities. In the following year the Army’s first concept capability plan was published and the term “cyber-electromagnetic” was coined to account for the overlap between cyberspace and the electromagnetic spectrum.[9] Shortly thereafter, the Cyber/Electromagnetic Contest Capabilities Based Assessment was completed, which identified numerous capability gaps and recommended priority solution sets (material and non-material) for further development or acquisition as applicable.[10] Strategic policy and guidance continued to evolve and cyberspace was designated as an “operational domain” in the 2011 Department of Defense Strategy for Operating in Cyberspace.[11]

In 2012, the mission command warfighting function was formally codified in Army doctrine.[12] One of the primary mission command warfighting tasks included, “Conduct cyber electromagnetic activities,”[13] subsequently referred to as CEMA[14]. The Army broadly defined CEMA as, “Activities leveraged to seize, retain, and exploit an advantage over adversaries and enemies in both cyberspace and the electromagnetic spectrum, while simultaneously denying and degrading adversary and enemy use of the same and protecting the mission command system.”[15]

In 2013, Joint Publication (JP) 3-12, Cyberspace Operations, was published, and it established a taxonomy and supporting lexicon for cyberspace operations. With overarching strategic guidance in place and cyberspace doctrine available for implementation, U.S. Army Forces Command (FORSCOM) developed and issued training guidance in this same year to guide Army forces as they incorporated cyberspace operations into their training plans and supporting training events.[16]

In 2014, Field Manual (FM) 3-38, Cyber Electromagnetic Activities, was published and specific to the exercise of mission command, this FM codified roles and responsibilities for commanders and staffs. Also, in 2014 the first Cyber Bulletin was published and it highlighted observations and emerging lessons learned over the most recent two years.[17] Finally, in this same year Fort Gordon, Georgia, was officially established as the U.S. Army Cyber Center of Excellence. The events described above provide a sampling of activities that in various ways have shaped the conditions in which commanders and staffs currently exercise mission command.

On Cyberspace Doctrine

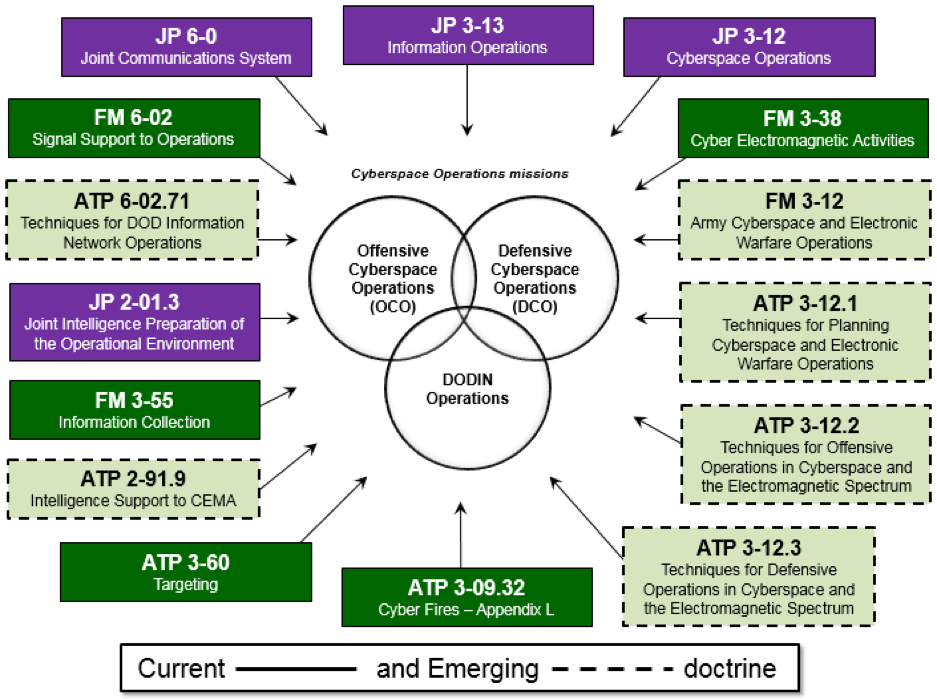

It is important to be aware of how doctrine is evolving and the impact this has on Army forces as they strive to operate in and through cyberspace. Cyberspace is defined in the joint community as “A global domain within the information environment consisting of the interdependent network of information technology infrastructures and resident data, including the Internet, telecommunications networks, computer systems, and embedded processors and controllers.”[18] Although JP 3-12 defines and thoroughly describes cyberspace operations, it is necessary for Army commanders and staffs to read additional doctrinal publications to gain a more holistic perspective on how and where cyberspace operations can be implemented throughout the operations process. The JPs depicted below in Figure 2 contain key information on cyberspace and cyberspace operations as promulgated by USCYBERCOM. The remaining Army publications represent current and emerging doctrine containing key tactics, techniques, and procedures addressing cyberspace operations.[19]

Figure 2. Current and emerging doctrine for cyberspace operations[20]

Collectively, current and emerging doctrine will guide commanders and staffs to more effectively lead and incorporate cyberspace operations into Army training and operations.[21] In particular, the draft FM 3-12, Army Cyberspace and Electronic Warfare Operations, currently in development, will provide detailed tactics and procedures for Army forces as they operate in and through cyberspace and the electromagnetic spectrum. The joint and Army doctrine previewed above represent a sampling of sources in continual development which inform the exercise of mission command in various ways.

Commander’s Role in Exercising Mission Command

With an appreciation of historical events and an awareness of a rapidly growing body of knowledge on cyberspace operations, Army commanders are able to assess their unique conditions and develop approaches to more effectively plan, coordinate, synchronize, integrate, and conduct cyberspace operations. Currently, commanders are having difficulty integrating cyberspace operations in support of their scheme of maneuver and overarching concept of operations. To varying degrees, they lack the personnel, equipment, and tactics, techniques, and procedures to conduct cyberspace operations.[22] The Army continues to identify and address these shortcomings through a concerted effort between the Cyber Center of Excellence, Army Cyber Command, and Army Cyber Institute.[23]

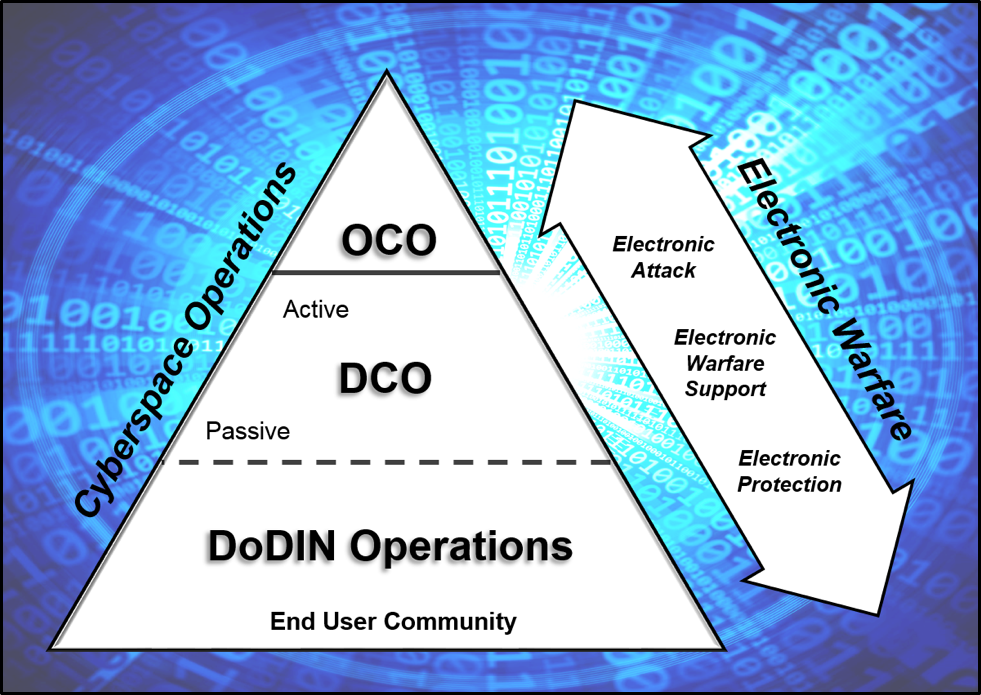

Cyberspace operations are described as missions in cyberspace and they include offensive cyberspace operations (OCO), defensive cyberspace operations (DCO), and DoD information network operations (DODIN operations). Depending upon the situation, these operations and associated capabilities may be combined with electronic warfare (EW), signal, information operations (IO), space operations, and intelligence to employ primarily nonlethal actions to create desired effects in and through cyberspace.[24] Figure 3 depicts the relationship between cyberspace operations and EW. The divisions of EW are depicted to provide a conceptual alignment of tasks.[25]

Figure 3. Cyberspace Operations and Electronic Warfare

Although commanders are limited in their ability to exercise mission command in and through cyberspace, they realize they have a key role in leading this effort. For instance, observations and emerging trends to date indicate that commanders are becoming increasingly involved in the planning process for cyberspace operations and their staffs rely upon them to address four focus areas. Specifically, commanders –

- Provide a clear commander’s intent and accompanying guidance for cyberspace operations to inform staff and subordinate actions throughout the operations process.

- Ensure active collaboration across the staff, with subordinate units, with higher headquarters, and with unified action partners to enable shared understanding of cyberspace and the associated opportunities and risks to military operations.

- Approve high-priority target lists, target nominations, collection priorities, and risk mitigation measures which reflect their visualization, description, and direction specific to cyberspace operations.

- Create massed effects by synchronizing the employment of cyberspace operations with lethal and other nonlethal actions (e.g., Fires and IO) in support of the concept of operations; anticipate and account for related second and third-order effects.[26]

The focus areas above illustrate the key role of commanders as they drive the operations process (i.e., plan, prepare, execute, and assess) and enable their staffs to conduct cyber electromagnetic activities.[27] These efforts will continue to confront obstacles and further require commanders and their staffs to demonstrate disciplined initiative to accomplish tasks involving cyberspace operations in support of unified land operations.[28]

Creating Shared Understanding

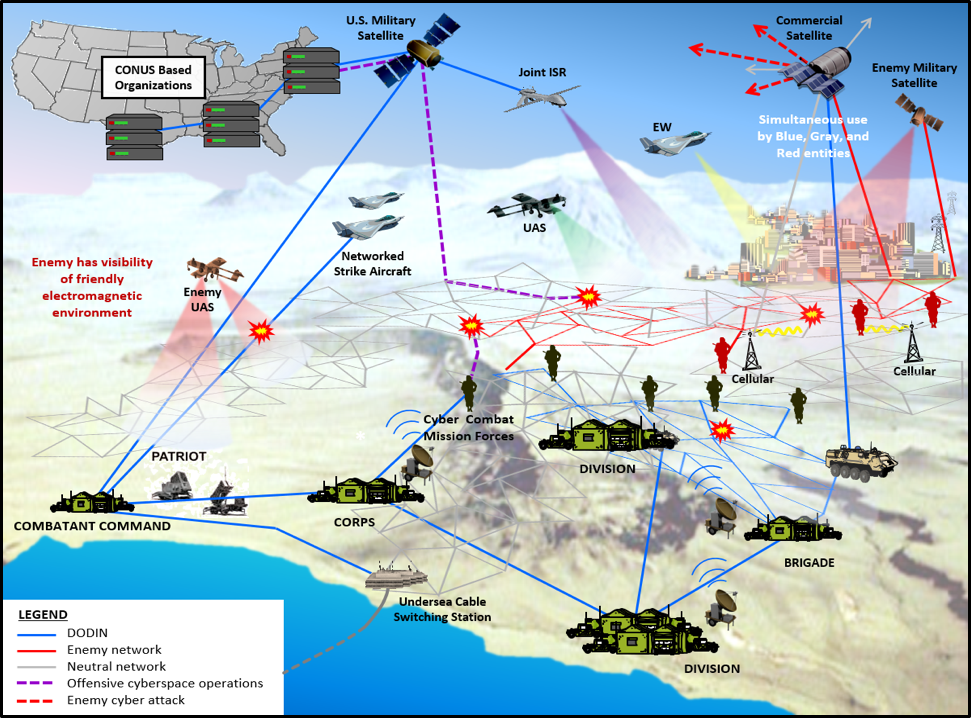

For effective integration of cyberspace operations, commanders apply the principle of mission command involving the imperative to create shared understanding.[29] Shared understanding requires commanders and staffs to engage in continual collaboration as they employ forces in a congested and contested operational environment. They collaborate to ensure their portion of the DODIN is secured and defended, while at the same time they gain and maintain situational awareness of enemy and adversary cyberspace activities.

While the incorporation of cyberspace operations into Army thought and action draws from the other principles of mission command (i.e., build cohesive teams through mutual trust, provide a clear commander’s intent, exercise disciplined initiative, use mission orders, and accept prudent risk), the holistic nature of cyberspace operations demands the creation of shared understanding which involves intense coordination, synchronization and collaboration.[30] Key to developing shared understanding, which in turn contributes to situational understanding of the operational environment, is the imperative to achieve cyberspace situational awareness. [31] Figure 4 depicts various elements that are considered in regards to cyberspace situational awareness.

Figure 4. Sample of Cyberspace Situational Awareness

Commanders and staffs create and maintain shared understanding in several ways. Internally, they ensure that battle rhythm events incorporate reviews of cyberspace operations in order to promote situational awareness and achieve unity of effort through collaboration. These battle rhythm events include not only planning events (e.g., Army design methodology sessions and the Military Decision-Making Process) but also briefings (e.g., update and assessment), meetings (e.g., operations synchronization), and working groups (e.g., targeting, CEMA and IO). Externally, commanders empower their staffs to collaborate with higher headquarters counterparts and unified action partners.[32] Ultimately, commanders and staffs strive to gain and maintain situational awareness of cyberspace which informs their overall situational understanding of the operational environment.

Implications and Conclusion

There are several direct implications for commanders and staffs as they seek to more effectively integrate cyberspace operations. First, they should embrace cyberspace as an operational domain and understand how this contributes to the Army’s focus and indeed reliance upon cross-domain operations.[33] Second, they should emphasize the importance of cyberspace operations as they drive or otherwise conduct the operations process in training settings and in combat operations. For instance, creating shared understanding of cyberspace is an essential aspect of mission command enabled by the DODIN which implies that commanders must ensure their portion of the DODIN is continuously operated and defended.[34] Third, they should establish reading programs to ensure their Soldiers are reading and implementing published doctrine as previewed in this writing. Additionally, they should expand their reading programs to include professional journals and other forms of joint and Army media addressing cyberspace and cyberspace operations. The Army Training Network and Cyber Center of Excellence Lessons and Best Practices websites maintain an abundance of tools for immediate download and use.[35]

Commanders and their staffs will continue to incorporate cyberspace operations into their training and operations despite numerous shortfalls. In the near future, many of these shortfalls will be addressed as a result of efforts by the U.S. Army Cyber Center of Excellence, the organization responsible for advancing “cyber, signal, and EW” in the domains of doctrine, organization, training, material, leadership and education, personnel, facilities, and policy (DOTmLPF-P).[36] During the interim, commanders will exercise mission command by driving the operations process and leading the conduct of CEMA, while ensuring that cyberspace operations are incorporated into organizational-wide thought and action.

ENDNOTES

[1] Mission command defined as “The conduct of military operations through decentralized execution based upon mission-type orders.” United States, Department of Defense, JP 3-31, Command and Control for Joint Land Operations, (Washington, GPO, 2014) IV-8. Army doctrine provides additional context for the decentralization aspect of mission command. Headquarters, Department of the Army, ADRP 6-0, Mission Command, (Washington, GPO, 2012).

[2] United States, Department of Defense, JP 3-0, Joint Operations, (Washington, GPO, 2011) II-2.

[3] “It is important to note that while mission command is the preferred command philosophy, it is not appropriate to all situations. Certain activities require more detailed control, such as the employment of nuclear weapons or other national capabilities, air traffic control, or activities that are fundamentally about the efficient synchronization of resources.” United States, Department of Defense, Capstone Concept for Joint Operations: Joint Force 2020, (Washington: GPO, 2012) 5.

[4] Capstone, 5.

[5] “Strategic Initiative 1: DoD will treat cyberspace as an operational domain to organize, train, and equip so that DoD can take full advantage of cyberspace’s potential.” United States, Department of Defense, DOD Strategy for Operating in Cyberspace, (Washington: GPO, 2011) 5.

[6] “Commanders conduct CO [cyberspace operations] to retain freedom of maneuver in cyberspace, accomplish the JFC’s [joint force commander] objectives, deny freedom of action to adversaries, and enable other operational activities.” United States, Department of Defense, JP 3-12 (R) Cyberspace Operations, Washington: GPO, 2012) 5.

[7] United States, Executive Office of the President, Cyberspace Policy Review: Assuring a Trusted and Resilient Information and Communications Infrastructure (Washington: GPO, 2009).

[8] Cyberspace Policy, 38.

[9] Headquarters, Department of the Army, TRADOC PAM 525-7-8, The United States Army’s Cyberspace Operations Concept Capability Plan 2016-2028 (Washington, GPO, 2012) iv.

[10] Malcolm Martin, Personal interview, 29 Jun. 2012. Regarding source – Headquarters, Department of the Army, Army Cyber/Electromagnetic (C/EM) Contest Capabilities-Based Assessment (CBA) Final Report, (Fort Meade, MD, 2011).

[11]United States, Department of Defense, Department of Defense Strategy for Operating in Cyberspace, (Washington, GPO, 2011) 5.

[12] Mission Command, 1-1.

[13] Mission Command, 1-4.

[14] CEMA acronym used for the first time in Army doctrine. Source – Headquarters, Department of the Army, FM 3-38, Cyber Electromagnetic Activities, (Washington, GPO, 2014) 1-1.

[15] Headquarters, Department of the Army, ADRP 3-0, Unified Land Operations, (Washington, GPO, 2012) 1-5.

[16] Headquarters, United States Army Forces Command, FORSCOM Command Training Guidance (CTG) – Fiscal Year 2014 (FY14) (Memorandum dated 12 Jun. 2013)

[17] Bruce Adams, Personal interview 12 Jun. 2014. Regarding source – Center for Army Lesson Learned, Brigade Combat Team Cybersecurity Operations: Trends, Lessons Learned, and Tactics, Techniques, and Procedures, Cyber Bulletin No. 1 (Fort Leavenworth, KS, 2014)

[18] Cyberspace Operations, GL-4.

[19] Christopher Walls, Personal interview, 13 Oct. 2015. Regarding a discussion on the proposed doctrine way ahead for cyberspace operations.

[20] Christopher Walls, Personal interview, 20 Nov. 2015. Reflects proposed/pre-decisional Army Techniques Publications (ATP) way ahead.

[21] Victor Delacruz, “Enabling Army Commanders to More Effectively Integrate Cyberspace Operations,” Cyber Compendium: Cyberspace Professional Continuing Education Course Papers (Wright-Patterson Air Force Base, OH, 2015) 110-118.

[22] Ricardo San Miguel, Personal interview, 18 Oct. 2015.

[23] Stephen Fogarty, United States Army Cyber Center of Excellence Strategic Plan (Fort Gordon, GA, 2015).

[24] Mike Scully, Personal interview 8 Nov. 2013. Regarding a discussion on the Army’s use of lethal and nonlethal actions as promulgated in doctrine. See also paragraph 6, page 22 of the 2014 Army Operating Concept. “The Army as part of the joint team conducts cyberspace operations combined with other nonlethal operations (such as electronic warfare, electromagnetic spectrum operations, and military information support) as well as lethal actions.”

[25] EA represents electronic attack, ES represents electronic warfare support, and EP represents electronic protection IAW JP 3-13.1, Electronic Warfare.

[26] L. D. Holder, Personal interview, 5 Jul. 2015. Building from the emphasis on combined arms maneuver, it is essential to consider cyberspace operations in the context of combat power as promulgated in ADRP 3-0, Unified Land Operations, 2011. 3-1.

[27] Mission Command, 3-3.

[28] Mission Command, 2-4.

[29] Mission Command, 2-2.

[30] Mission Command, 2-1 to 2-5.

[31] Cyberspace Operations, IV-5

[32] Unified Land Operations, 1-3. “Unified action partners are those military forces governmental and nongovernmental organizations, and elements of the private sector with whom Army forces plan, coordinate, synchronize, and integrate during the conduct of operations.”

[33] Headquarters, Department of the Army, TRADOC PAM 525-3-1, The United States Army Operating Concept: Win in a Complex World, 2020-2040 (Washington, GPO, 2014) iv.

[34] Strategic Plan, 2.

[35] Army Training Network, Army Cyberspace Operations and Cyber Electromagnetic Activities URL: https://atn.army.mil/dsp_template.aspx?dpID=460; Cyber CoE Lessons and Best Practices URL: https://lwn.army.mil/web/cll/home; See also “What’s Hot” and “Training Bulletin Board” on the ATN base page.

[36] Strategic Plan, 5. “Priorities and Objectives: The Cyber CoE is the US Army’s force modernization proponent for cyberspace operations, signal/communications networks and information services, spectrum operations, and EW. As such, it is responsible for developing the underlying concepts and refining processes for identifying, training, educating, and developing world-class, highly-skilled professionals supporting strategic, operational and tactical cyberspace, signal, and EW operations.”